A view of Red Warrior Camp from across the stream. It’s tough to really do the size of the camp justice. Photo by Sven Jorgensen.

Inside the Community Blossoming at Standing Rock

I pulled up to the gate at Sacred Stone Camp on the Standing Rock Reservation on a sunny, cold late summer day in Cannon Ball, North Dakota. Spray-painted plywood signs near the entrance reminded visitors that no alcohol or firearms were allowed in the camp, and a massive blue tarp stretched over a metal frame created a lumpy “security tent” by the side of the road.

A friendly-looking olive-skinned man with tousled black hair squinted at us in the low rays of the setting sun. “You guys been here before?” he asked my friend and me, as if he might recognize us.

We hadn’t, but he welcomed us to camp anyway, giving us directions to the kitchen and letting us know that no photos or video were allowed on site. A multi-colored array of tents and cars greeted us as we pulled down a steep dirt hill into the campground, as well as several large, white canvas teepees with long wooden poles fanning out in neat circles from their pointed tops.

Flags from all the tribes that have converged at Standing Rock line the entrance to Red Warrior Camp. Currently there are over 300, and counting. Photo by Sven Jorgensen.

Dust, smoke and the smell of food were in the air. Sacred Stone is one of two main campsites on the Standing Rock Reservation, which is now hosting over 3,000 self-labeled “protectors” who have gathered with the intention of stopping construction the Dakota Access Pipeline, intended to transport 450,000 barrels of crude, fracked oil per day from the Bakken fields of North Dakota to Patoka, Illinois.

The activists, whose population now includes delegations from over 300 indigenous tribes from around the globe, refuse the identity of “protesters,” so often attributed to them by the mainstream media. Rather, they assert the root of their cause to be protection — of the land, the water, and ultimately of all life.

One Native American man addressing the group at a campfire on Wednesday said it best: “We have to protect each other. You see these signs here, they say ‘protect the sacred’, but that doesn’t just mean the sites, or the ceremony. That means each other, each one of you are sacred, your life is sacred. When we’re here, we’re here in ceremony, all day, every day.”

Over the past month, national and global awareness of the events in North Dakota has increased, and the camp population has swelled. On Sept. 9, tribes lost a federal court action intended to block construction. Then the Obama Administration put a temporary halt to pipeline construction at a spot close to the Missouri River that had been the scene of several protests.

The administration’s decision was portrayed by most media sources as a climax, and as a victory for the Sioux and the anti-pipeline activists. If you’d been following the story from afar, you might expect to feel a celebratory air at camp, or to see an exodus of activists. But in fact, there is neither. The Native Americans coordinating the effort see the Administration’s announcement as a minor win at best, and a deescalation tactic at worst — and they are preparing for a battle that is just beginning.

“People think that announcement means nothing is happening anymore, but actually there’s still lots of construction going on lots of places,” said Kandi Mosset, a representative from the Indigenous Environmental Network who was at the media tent when I stopped by. “People are still getting arrested almost every day.”

In fact, 22 people were arrested on Sept. 13, the day I arrived, including two members of the press: here’s the ominous video from Unicorn Riot of the events that day. Eight more were arrested the next day, and both days the arrests took place in the presence of police with automatic weapons.

Yet back at camp, there is little discussion of the news: what I witnessed is a communal, focused effort of keeping up with essential daily tasks, and creating a sustainable living space for a long-term engagement.

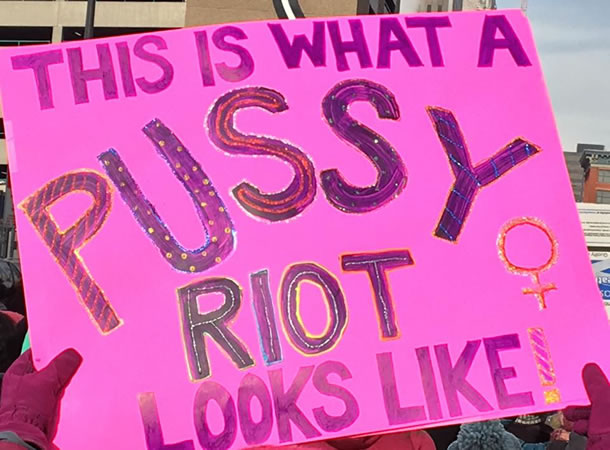

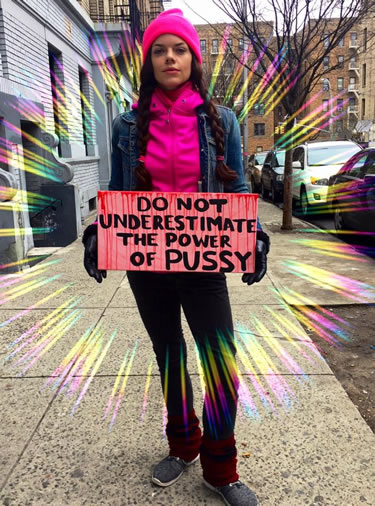

A solidarity march from Sept. 4 joined by almost all campers and activists. Photo by Dallas Goldtooth, from www.ecowatch.com.

A woman named Lisa, from the Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota, was camped near me in a teepee with her family. They had come up a week or so ago. When I asked how long they were planning to stay, Lisa’s 10-year-old-son jumped in, “Til it’s over!”

Most media reports on the protests in Standing Rock have come from the sites of direct actions, the spots throughout the reservation where construction is being attempted and where civil disobedience is carried out. It’s easy for the public to miss the domestic side of this historical gathering: the massive campsites where hot food is freely available throughout the day, where the constant influx of donations from around the country are sorted and stored and where cultural bridges are continuously being built and crossed.

The camp kitchens are a fascinating sight. At the larger camp, known as Oceti Sakowin or Red Warrior Camp, the appearance is actually more reminiscent of a thrift store, or a giant garage sale, except there is no money exchanged. Dozens of tables are lined with overflowing boxes and bags of donated clothing — mainly coats, sweaters, and other winter items. On the ground are stacks of children’s items, including books, toys and a huge bucket of crayons.

In the background, new donations are being sorted; we watched as a load of supplies including bulk toilet paper, sleeping bags and several family-sized tents, brand new and still in their boxes, were unloaded and stored.

Both camps serve hot meals regularly every day. At Sacred Stone, the smaller spot where I stayed, you’ve got to show up at mealtime. At Red Warrior, the kitchen was offering fresh pasta with cheese, sauce, veggies and garlic bread at 3:30 in the afternoon. I peeked into a few of the storage tents and saw floor-to-ceiling stacks of bags of rice and beans in one, hundreds of canned veggies, fruits and more in another. Outside were packages of water bottles stacked four or five high as they were unloaded from a large truck.

Overflowing boxes of donated winter clothes at Red Warrior Camp. Photo by Sven Jorgensen.

Again, one gets a sense of a long-term plan.

Next to the kitchen at Red Warrior is a campfire that never goes out, and a community microphone: announcements are made over the loudspeaker all day long and late into the nights. The arrival of new tribal delegations are announced there (a group from Ecuador had just arrived Wednesday) and ceremonies of various sorts are often held. Elders and community leaders take turns speaking to the camp and giving updates and insights throughout the day.

I didn’t catch the name of the Native American man (quoted at the beginning of the article) who was speaking when I dropped by, but he was talking about the arrival of armed policeman at the action sites, and of the need for all protectors to behave with utmost respect.

“The police were unarmed before, but now we’re seeing men with weapons. We have to pay attention. These are signs,” he said. “We have to watch how we conduct ourselves.”

“What we do directly reflects on the rest of the camp, and all our youth are looking at us and learning from us. Our children come first. That’s why we’re here, that’s why we’re protecting this water. We’re all going to be gone in the blink of an eye.”

I found out from Kandi Mosset that action sites are decided upon each day by a tribal council, and that anyone who wants to participate is asked to wait around the fire in the morning for an announcement.

A month ago, with only a couple hundred protectors on site, camp would empty on action days. Now, Kandi told me, “most people at camp won’t know that there’s an action going on,” or where it’s taking place. I’d missed the call for action that day, but I visited the spot just half a mile up the road where, less than two weeks before, construction had been attempted on a sacred burial site, and where private security forces had unleashed attack dogs and used mace on protectors. (It’s also the area where Democracy Now! reporter Amy Goodman has been accused of Criminal Trespassing; on Thursday, Sept. 8, the state of North Dakota issued a warrant for her arrest.) There is now a makeshift camp by the side of the road, with its own kitchen, campfire and occupants, who have taken up the duty of watching over the freshly exhumed land.

A woman named Jolene told me that at the end of August, the Standing Rock Sioux had submitted a map to the Army Corp of Engineers that showed the areas of land considered most sacred. Then on Sept. 3, a Saturday, bulldozers “suddenly showed up here, 15 miles south of where the rest of the work is being done.”

“It was just to antagonize us, a bullying tactic,” she said.

Activists set up the roadside camp after Democracy Now!’s video of the dogs and pepper spray went viral. Native tradition prohibits photo and video of ceremony, prayer and sacred ground (particularly in this raw condition) so the 10 or so campers here are diligent in preventing visitors from taking any pictures.

Disregarding the tradition, given the already painful fact of the destruction of the burial site, “is just like, kicking them while they’re down,” said one of the men guarding the entrance to the camp.

Back at Sacred Stone, people were winding down after a day of preparing for rain that was predicted to arrive overnight. Several larger, sturdier shelters had been constructed, loose donations moved into them, and piles of wood chopped for fire. At night we sang around the fire in the kitchen, led, coincidentally, by the musical group One Tribe, with whom I traveled on the UpToUs Caravan, and who have been in North Dakota since early August.

The rain came, tapping gently on the tent roof overnight and picking up as we gathered for breakfast. While campers ate or huddled over mugs of hot, strong coffee, an elder called Uncle Robert started to speak. Uncle Robert is a camp fixture: you can see a Young Turks interview with him here. He’s got dark, leathery skin, a husky voice, and an enormous heart that spilled over into tears from his eyes all three times I heard him address the group.

I took my phone out to record, but then realized I shouldn’t; his words are always a prayer.

He talked about being an American, the fact that Natives have fought in wars overseas with the United States, that the Native spirit is aligned with the American ideals of freedom, community and respect. He talked about the convergence of the tribes, the necessity of unity. And he talked about being amazed by the turnout of Americans showing up in solidarity to the camp, how everyone who’s come has “good hearts.”

When we left soon after I felt a deep sense of humility and gratitude, something that was growing inside me during the entire experience. The Natives are fulfilling a prophecy: they are heeding a call, living out a karma they’ve accepted. As a Caucasian, I am blessed to have a chance to witness it.

Yet I too drink water, and I too feel the pain of the Earth. Ultimately, this is a universally human battle, with an outcome that could touch us all. And there will be more battles to fight. We will need to make mainstream the spirit of collaboration and sacrifice found at Standing Rock.

As Eric mentioned on Planet Waves FM last week, the astrology shows signs of revolution brewing — and this is a revolution that anyone can take part in. New campers and activists are pouring into Standing Rock every day. Cultural walls are coming down, both between the individual Native tribes and between the Natives and outsiders. There is leadership, organization and a practical fusion of tradition and modernity (for example, the limitation on film and video with respect to Native customs manages to be combined with a very active social media presence.) There is an awareness, so often lost in our ‘every man for himself’ world, that this cause transcends individual survival.

Are you a lawyer? A mechanic? A gardener? A carpenter? An artist? A teacher? A chef? Go out for a week. Approach with humility and respect, and your expertise will be welcome. You can contribute to a cause that is universally significant in dozens of ways. The experience of humanity you will receive in return is likely to change your life.

———————-

For more information about Sacred Stone Camp, visit their website. To make a financial contribution to the Legal Defense Fund, visit here. To learn about visiting, donating supplies and local resistance actions happening around the world, visit here.