By Steve Guettermann

According to my understanding of Buddhist tradition, the human mind is incapable of understanding the Great Originating Mystery, so Buddhists don’t spend time contemplating it. It may be that the human mind cannot fathom human existence on this singularly beautiful planet, as well. So, the reason as to why we are here may escape us until we reach a higher level of consciousness, which may be possible only by caring for our planet and one another. Hence we live in a quandary: we are to care for our planet and one another, yet lack the mental capacity to know why.

The three major pyramids in Giza, Egypt. From left to right, the Pyramid of Menkaure, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Khufu (also known as The Great Pyramid). Photo by Mark Fischer / Flickr under Creative Commons.

Conscious human evolution, that is, evolution by choice rather than chance, is the tool we have to unlock the secrets of life and release ourselves from this quandary.

Among the benefits of modern technology, which is, in itself, a mixed blessing, is that technology can afford us the space and time to make personal transformation. Yet, a technology that separates us from what gives us life, rather than enhances our relationships with what gives us life, likely does not serve conscious evolution.

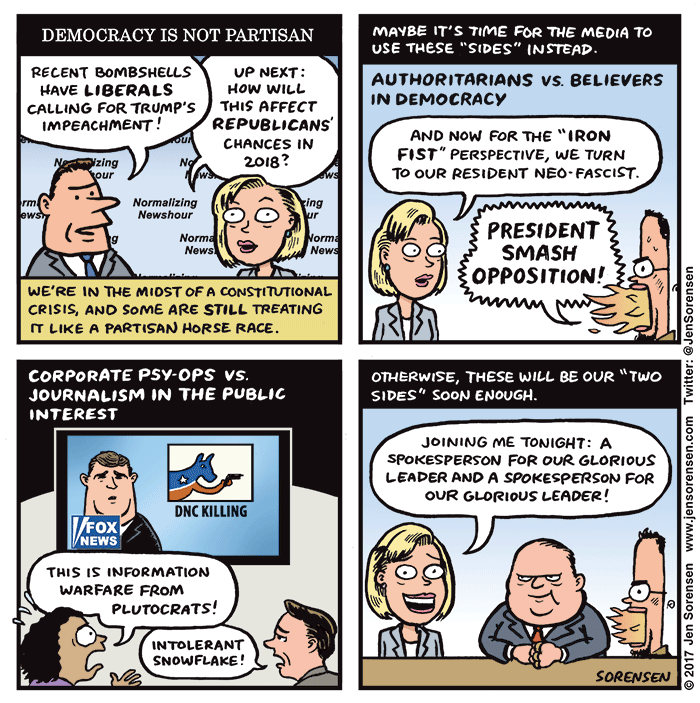

Let’s take a quick look at some indigenous technology. When I ask students for examples of that, they usually come up with things such as bows, arrows, spears, atlatls and stone knives. When I ask students to think big or beautiful, they can’t. So I’ll draw a pyramid on the board and say, “This is an example of indigenous technology.” I may show a photo of jewelry from a tomb and say, “This is an example of indigenous technology.”

The later examples used processes we still do not understand. In 1978, Nippon Corporation failed when trying to build a scale model of the Great Pyramid of Giza without its complex interior. The goal was to use only primitive tools and techniques. Choosing a site near the Great Pyramid where they could quarry limestone, they went to work.

They could not cut the limestone blocks from the quarry without jack hammers, could not transport them across the Nile and sand without steamboats and trucks. Cranes and a helicopter were used to position the blocks. Nor could engineers bring the corners into alignment, even by using lasers for leveling. Yet the builders of the Great Pyramid evidently had the answers. Some suggest they used complex mathematics that relied on the sun for accurately leveling the site.

Like the Egyptians, the Inca were also known for their stonework, creating huge ceremonial and civic structures with virtually no space between the joints of rock. As for metalworking, some processes used in antiquity to create jewelry, especially gold jewelry, still cannot be duplicated today.

Among my favorite examples of indigenous technology are stone knives. Photos from electron microscopes show obsidian (and maybe flint) knapped blades to be sharper and perform better than surgical scalpels, although the FDA does not approve stone blades for surgery. Several times, when I Sun Danced and was cut with scalpels, I wondered how much less painful it would be with a flint-knapped blade, but it was not to be.

Technology should enhance our connection with the planet, rather than separate us from it. Connection is what indigenous technology accomplished, accomplishments and technologies moderns have not completely deciphered. I’m no proponent of capital punishment, but I am amazed that hemlock’s most famous victim, Socrates, seemingly tossed back a cup of it and was quickly released into Hades. Today, despite a palette of pharmaceutical death drugs, the job is frequently botched. Are we so dead-set against the efficacy of plants and to the indigenous knowledge of their uses that to acknowledge them as a legitimate choice to pharmaceuticals somehow undermines reality?

The point is that indigenous technology intimately connected the user to the world, or in Socrates’ case, the Underworld. The pointlessness of much modern technology is that it is designed to separate us from what gives us life, as well as from one another. It makes us oblivious to the obvious; oblivious to the miraculous.

This was really brought home the other day. It was a perfect spring afternoon in Montana: temperature in the low 70s, azure, cloudless skies, no wind, beautiful plants, and sweet-smelling air. This was right after a rain. Petrichor is the pleasant smell that frequently accompanies rain after a long period of warm, dry weather. According to LiveScience it has two causes:

“Some plants secrete oils during dry periods, and when it rains, these oils are released into the air. The second reaction that creates petrichor occurs when chemicals produced by soil-dwelling bacteria known as actinomycetes are released. These aromatic compounds combine to create the pleasant scent when rain hits the ground.”

Like the fragrant scent from a flower, petrichor is a way the earth thanks the sky for rain.

There is something truly mesmerizing of the diversity embodied in the blues and greens of spring. I’m convinced those colors look better this time of year than any other. When I stepped outside yesterday and took it all in, I resolved to match my mental-emotional state with the natural. I would feel only good and have only good thoughts, acknowledging that the sun shone equally on all.

Sun through post-rain trees; photo via YouTube.

Nothing in me would disrupt the sweet-smelling, vital energy out there. I would not adulterate perfection. It would all be as it should be during my entire nine block walk to the co-op downtown and back home.

It was, until I walked a few feet. Then, car exhaust knocked me off center. However, it was the look on the driver’s face that gave me pause. Seemingly he was not having a perfect day, although he seemed to have a perfect car. He flipped me off.

“He’s probably upset he’s not walking,” I thought.

I had to re-center myself a few more times before I got to the store, but practice and a perfect day made it easier each time. Once was at the Federal Building, where a man was spraying chemical lawn treatment with no hazmat protection. That would likely be bad for business. The acrid smell of liquid chemical fertilizer burned my nose; the drone of the pump on the back of his truck blotted out the bird songs. I said a little prayer for sprayer man and went on.

I had a delightful discourse with the co-op cashier, then took the long way home, all of an extra block. Bozeman is a small town by American standards, but it can have big-city traffic behavior, especially during “evening rush hour.” So I waited at the crosswalk on a two-lane one-way street for traffic until a pick-up truck finally stopped so I could go. In Bozeman, that does not mean it’s safe because the traffic in the other lane almost never responds to a vehicle stopped near a crosswalk.

Isn’t that interesting? A truck is stopped in the intersection, blocking the crosswalk from the view of traffic on its right — in this case — yet that traffic never, ever seems to consider that the truck is stopped because someone might be crossing the street. So a second vehicle would have run me down, but I stopped in the middle of the crosswalk. The driver pretended not to notice me as she zipped by a few feet from my feet. I am pretty sure if we don’t look at one another, it’s easy to convince ourselves there’s no one there. I smiled at her anyway, flashed the peace sign to the truck driver and enjoyed the rest of the walk.

Montana is still fortunate enough to have grizzly bears and I spend a fair amount of time in the mountains. While grizzlies are nothing to mess with, and maulings happen, most bears don’t cause problems. Yet in a twenty-minute walk I was flipped off, poisoned and almost run over, all by my own kind on a perfect day. It makes being in grizzly country all the more relaxing.

It seems to take a 24/7 onslaught of negative stimuli and distraction to keep us divided. On the other hand, it would take little positive input to get us to realize our connections with one another and the planet if we weren’t inundated by divisive messaging. I think this impending realization is the great fear of whatever wizard is behind the curtain of fear mongering. Realizing our connection is the crux of conscious evolution. Keeping us separate is the anti-thesis. By taking care of our planet and one another, mystery and wisdom are revealed. Even if I’m wrong, it’s a nice thought.

Another thought is that modern technology keeps us from doing much of what we can do for ourselves. Now, that is quite a statement. Yet from my experiences and studies I’ve come to that conclusion. From telephone and internet communication, to travel, healing, navigating in the dark and finding lost people, many of us have successfully practiced these techno-abilities simply using our human abilities; indigenous shamans and shamanesses are even more proficient.

So the question is, “Why do we invest in and embrace technologies that can do no more than we can do?” For an excellent, well-researched exploration of this question, I suggest the book Spirit Talkers, by William S. Lyon, PhD. I am not saying there are no benefits to modern technologies. I am saying they should not be foisted upon us by undermining our talents and common humanity, or at the unsustainable expense of the planet. That’s all.

This brings us back to life on Planet Earth and the tumult of our times. The chaos is so encompassing that it simply has to be contrived. Nothing can be this whacko without Undivine Intervention. So what’s going on?

I don’t know, but I sense we neither understand the importance of our planet nor our being here. Obviously our singularly beautiful planet is special. So, if we are here, we must be special, too. We aren’t special because we are special, though. We are special because we are equal.

For some reason, we have chosen to make ourselves unbelievably miserable while desecrating this rare space jewel, rather than consecrating her with our activities and creativities. While we may not pose an existential threat to our own consciousness or to the planet — one way or the other both will survive — we do pose one to our happiness and evolution. Peruvian shaman don Oscar Miro-Quesada is fond of saying, “More than saving the planet needs loving.” I think the same goes for us.

Yet, the time and energies suggest we have the opportunity to make a quantum leap of evolutionary understanding if we make use of the time and galactic energies available now. So, there may be no existential threat, but there is a choice.

We can be happy, fulfilled and conscious now, and live in harmony with one another, our planet and the eight and a half million species we share her with, and undertake a mutual journey of conscious evolution to new dimensions; or we can choose to be even more unhappy and miserable than we are now, strangely apathetic at the prospect of sludging through 25,000 years or so before we have a comparable galactic alignment and energetic boost as is available today.

I think it’s time for some immediate gratification.

A note from Steve on The Petrichor Practice:

The next time you go outside after a cleansing rain — and I know there are some intense storms going on in parts of the world so some may have to wait — simply connect and embody petrichor’s natural purity. If you can do this under clear skies, day or night, so much the better. Take it in. Consciously and completely fill your mind, body, spirit, emotions and soul with it. Keep at it until you feel a very real and strong sensation and transformation. Then simply intend to energetically share this, without holding back, to everything in your life for a few minutes, an hour or all day. Reboot as often as necessary.

Steve Guettermann is a freelance writer and “teaches” critical thinking at Montana State University. He is currently studying Peruvian shamanism under don Oscar Miro-Quesada, and published an article in last year’s Planet Waves annual edition, Vision Quest. Steve’s email is migratoryanimal@gmail.com; you can also visit his website.