North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory has declared a state of emergency in the city of Charlotte, where protests continued for a second night after Tuesday’s fatal police shooting of 43-year-old African American Keith Lamont Scott, the father of seven children. Police say Scott “posed an imminent deadly threat,” but Scott’s family says he was unarmed. Corine Mack, president of the NAACP Charlotte-Mecklenburg Branch, and Bree Newsome, Charlotte-based artist and activist, both call for the release of the police video of Scott’s killing. “There has to be transparency,” Newsome says. “This distrust that exists between the police and the community is completely well-founded.”

Democracy Now! is a national, daily, independent, award-winning news program hosted by journalists Amy Goodman and Juan Gonzalez.

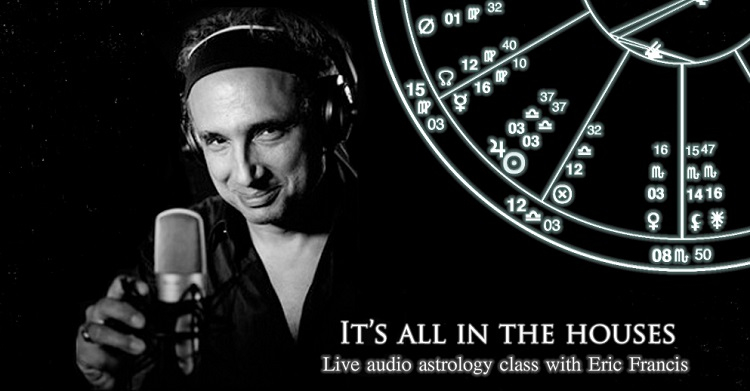

This live audio class covers the most basic level of astrology: where things happen, the houses. If you understand the houses as environments and groups of themes, you can read a chart. We will hold the class by teleconference at noon EDT on Saturday, Oct. 8, 2016. You may sign up here.

On a related topic, this was posted to FB on Sept 21 by a woman named Rebecca Lee; apparently she teaches in a school in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where the daughter of Terence Crutcher attends. Crutcher was shot by a female (white) police officer on Sept. 16: