Flying Over Tycho. Tycho is the well-known landmark crater of the southern lunar hemisphere, visible here just below the plane’s nose. The crater’s impact rays are believed to extend well into the lunar northern hemisphere. Photo by Anthony Ayiomamitis.

Editor’s Note: Gary Caton is a specialist in observational astrology — an earlier kind of navigation by the stars and planets that depends on what you can see. He will be doing our Full Moon article each month teaching this method, telling you about what is visible in the night sky. Anthony Ayiomamitis is our friend in Greece, and he is a photographer-astronomer who often takes photos near the ancient temples that dot the land of his country. I consider him an honorary astrologer. — efc

Traditionally, the Full Moon closest to the fall equinox is called the Harvest Moon. The idea is that for a few days the light from the Full Moon allows farmers to work later, and helps them to bring in their crops. Because of the shallow angle the ecliptic (the path of the Sun, Moon and planets) makes to the horizon at this time of year, the extra natural light from the Full Moon is maximized. Normally the Moon rises 50 minutes later each evening, but at this time of year it is only about 30 minutes. So, there is no long period of darkness between sunset and moonrise and farmers can continue being productive, bringing in their crops by moonlight even after the Sun has set. Hence we get the name Harvest Moon.

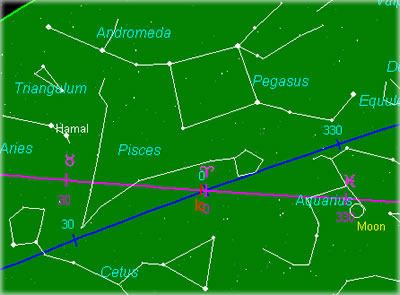

Star chart showing the constellation Pegasus, with Cetus, the sea-dragon, partially shown at the bottom. Andromeda, the princess, is partially shown at the top; it shares its brightest star with the Great Square of Pegasus. The purple line is the ecliptic.

Visually, the most noticeable thing about this Full Moon is that it has passed by the Summer Triangle, and is now shining under another huge asterism (a grouping of stars that may or may not form a constellation) called the Great Square of Pegasus. Pegasus is an easy constellation to find in the autumn sky. The constellation forms a winged horse, which is flying upside down across the sky. Begin by looking for the four stars of about the same brightness that form an almost perfect square or diamond. This is the Great Square, which represents Pegasus’ body. Next, start at the lower right corner of the Great Square and continue your gaze to the right and down along Pegasus’ neck and then slightly upward to a brighter star. This bright star is Enif, which represents Pegasus’ muzzle or nose.

Enif happens to be an integral star in the Sibly chart for the U.S., as it is shining above the Moon in late Aquarius. The Sibly chart is one of the more commonly used birth charts for the U.S., based on the signing of the Declaration of Independence. We’ll get back to the specifics of this later.

The stars of Pegasus shine above the part of the Zodiac that stretches all the way from late Aquarius, through Pisces and past the vernal point into Aries. Anytime we have planets right below the individual stars of Pegasus, this is considered a conjunction. When we see these conjunctions we should be alert for the signs of a psychological complex called “The Pegasus Syndrome,” which is a set of behaviors that echo some of the mythic themes surrounding one of the winged horse’s unfortunate riders.

Pegasus was the offspring of Medusa and Neptune. The winged horse was born from the mix of sea foam and blood when Perseus tossed Medusa’s severed head into the sea. Early in the myth, we see references to three other constellations nearby Pegasus in the sky: Perseus, Cetus and Andromeda. The story goes that Perseus rode Pegasus, who carried the hero over the sea to defeat Cetus, the sea-dragon, and rescue the Princess Andromeda.

After this, the young colt was taken by Minerva (Athena) to Mt. Helicon and his care entrusted to the Muses. He was the favorite of Urania, the Muse of Astronomy (and presumably astrology as they were not separate then). It then happened that another hero, Bellerophon, was called on to slay the Chimera, a beastly mixture of lion, goat and dragon. Bellerophon accepted the challenge and consulted the soothsayer Polyidus, who advised him to procure the help of Pegasus. For this purpose Polyidus directed Bellerophon to pass the night in the temple of Minerva (who was the patron of heroes), and as he slept Minerva came and gave him a golden bridle. Minerva also showed him Pegasus drinking at the well of Pirene, and at the sight of the golden bridle the winged steed came willingly. Bellerophon mounted him, and gained an easy victory over the monster.

Bellerophon riding Pegasus attempts to fly to Olympus. This ceiling fresco by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696-1770) hangs in the Palazzo Labia, Venice, Italy.

Bellerophon spent many long years and accomplished many heroic deeds in the companionship of Pegasus, but in the end fell victim to the tragic flaw of hubris. Bellerophon attempted to fly up into heaven on his winged steed, but his pride and presumption drew the anger of the gods. Jupiter sent a gadfly, which stung Pegasus and made him throw his rider. The winged steed went on without him to become immortalized in the sky.

From this, we can gather that the Pegasus Syndrome is about people who are, on the one hand, blessed with divine aid and an ability to negotiate difficulties by rising above them. On the other hand, their success carries the danger of overreaching themselves.

In the story, Bellerophon unwisely attempted to fly to Olympus (overreach his potential). After achieving success, which was not entirely his alone, he took himself too seriously and mistakenly believed that Pegasus was subject to his will. However, it was Pegasus who made it to Olympus, and Bellerophon who fell. The moral of the story is that it is unwise to overestimate your abilities or take for granted a partner as the ‘lesser’ person, whom you can control. So, the Pegasus Syndrome is at once the seemingly blessed ability to ‘fly over any situation’, with the caution of reversals or lessons in humility — being ‘taken down a peg or two’.

As mentioned earlier, the brightest star in the constellation Pegasus shines above the Moon in the U.S. Sibly chart. Do any of these mythic themes sound vaguely familiar with regard to the United States as a nation: an heroic figure who achieved many significant victories, but then overreached and got knocked down a peg or two? After WWII the U.S. was the only nation to be both victorious and survive with its infrastructure intact. This put us on the course to become a superpower, both a financial and political hegemon. Since then, however, flying all over the world as a sort of world police has not worked out so well. While technically we can claim victory in the Cold War, we definitely got knocked down a peg in Vietnam, and the jury is still out on Afghanistan and Iraq. It’s a mixed bag at best. In this astrologer’s opinion the U.S. might even be the poster child for the Pegasus Syndrome, and as I have written elsewhere, should consider taking a more cautious approach toward both world relations and resources.

But what does all this have to do with you and me? In my missives on both the June and July Full Moons, I showed how in the summer months the Full Moon is illuminating the Summer Triangle and the mythic journey of the Hero/ine — inviting us to ‘live like stars’. Now, as autumn approaches, the Full Moon is lighting up a part of the sky that warns us of the consequences of taking this heroic journey too far. If the hero/ine doesn’t know when to call it a day, a season or a career, then the victory/treasure may be spoiled or lost. The Tao Te Ching sums up this wisdom in verse 44: To know when you have enough is to be immune from disgrace; to know when to stop is to be preserved from perils.

Depending on your circumstances, it may be time for you to take up one or two last adventures before summer officially ends, but if you venture forth, be aware of the dangers of flying too high or overreaching. If you are tempted to take on an epic adventure which requires great risks, it may be better to put it off until a time when you will have the opportunity to follow up with a second or third chance. It may also be time to simply call it a season and reflect on the lessons in the adventures you’ve already encountered. In either case, the message in the heavens just now is that when living like stars, we must still remain cognizant of our own mortality and fallibility, and not take foolish chances or indulge in self-aggrandizement.

P.S. If you are interested in contributing to the 2012 annual edition, please visit this page.