Dear Friend and Reader:

The translator was laughing so hard he could not speak. He seemed to have heard the funniest thing in his life. We were all waiting for the English version of what Ogyen Trinley Dorje, the Tibetan Buddhist leader known as the 17th Karmapa, had said.

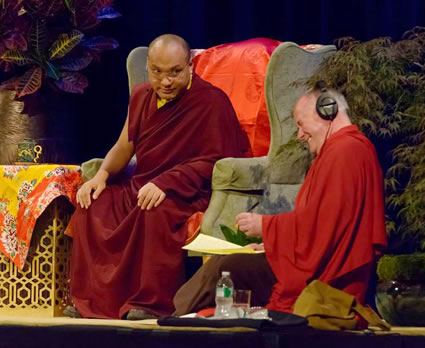

Lama Yeshe Gyamtso, the translator at right, cannot contain his laughter at a comment the Karmapa has made about the weird things people bring home from Tibet. It seems he’s seen some of those suitcases get packed. This and all photos below are courtesy of Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism; photographer credit is given where known.

The monastery up in Woodstock, New York, is the Karmapa’s North American base. He was here on his second visit to the U.S. on April 18.

The translator, Lama Yeshe Gyamtso, tried to compose himself, but without much success.

He finally seemed to find his center, then after taking about two breaths, he burst into laughter again.

Laughing like the Buddha himself, wrapped in his bright red robe, which the color of his cheeks now matched, sitting at the Karmapa’s feet in his headset with pad and pencil still in his hands.

Not your average stone-faced interpreter, the kind who can never let on that they’re actually listening to what they translate.

Dorje, for his part, was placidly watching this scene, mildly bemused. By this time the audience was getting the giggles. I am one of those people who notice moments of actual transcendence and this was one of them. You never see scenes like this in the presence of an international dignitary — well, hardly ever.

Finally the Lama Yeshe could speak. “The sad part is, it won’t be as funny when I translate it.” Still, everyone wanted to know.

One persistent theme of Dorje’s talk was urging caution around religious traditions, especially if they’re adhered to mindlessly for their own sake. In that context, he was explaining that there are certain traditions that don’t help the cause.

For example, if you visit Tibet and come home with a souvenir skull and put it on your altar, it might frighten your family and make them think you’re into something really weird. They would not have an accurate notion of your practice. So you don’t have to do that kind of thing.

That, for whatever reason — the teacher’s inflection, or some reference into his personal experience — is what the Lama Yeshe just could not contain himself over, because of how funny it was. You can only imagine why that tickled his funny bone. He’s probably seen a few people bring home some really weird things from Tibet.

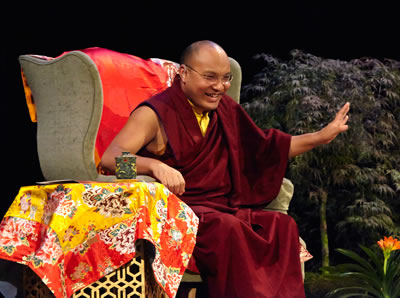

His Holiness Ogyen Trinley Dorje, the 17th Karmapa, greets the audience before the refuge vow ceremony at Ulster Performing Arts Center on Saturday, April 18. Photo by Robert Hansen-Sturm.

Dorje is known as a young, up-and-coming Tibetan leader who is actually with it. He’s just 29, he follows and talks about current events, and as far as I could tell, he has a clue what people are facing at our time in history.

There is a tradition in Tibetan Buddhism of offering practical information that one can actually use, rather than complex, abstract spiritual theories that seem neither to have feet nor touch the ground.

Dorje had a lot to say about the difference between religion and spirituality. This seemed to be the dominant theme of the day’s teaching.

As he understood the terms as currently used in the United States, he explained, religion is what you do because it’s handed to you by tradition or by your family. You don’t necessarily know why you do it, or what it means.

Spirituality, by contrast, involves a process of personal exploration and direct experience of life. It’s not about following the choreography of tradition; rather, you dive into a journey, make discoveries and actually learn what works for you.

People who have unusual spiritual experiences often get the attention of others, but then their direct experiences are typically codified into religions, and the seed experience is typically forgotten. He offered what he called an imperfect metaphor.

Imagine that the Buddha is in a hall, speaking to his disciples. He finishes speaking and says that the only way out of the hall is to his right. Then he leaves, to the right (experiencing what in context seemed to be a Tibetan word for enlightenment). His followers, though, stay behind in the hall, for hundreds of years.

They remember what the Buddha said about only exiting to his right, and that he walked out of the hall that way. What they don’t know is that he said that because there wasn’t a door on the left.

Lama Yeshe Gyamtso, one of the Karmapa’s two translators, is a beloved figure among Tibetan Buddhists of his lineage. He could be Buddha. Photo by Robert Hansen-Sturm.

Now, many years later, there is one, but nobody is paying attention to the original intent of the teacher’s words. First “exit to the right” becomes a rule, then a religious dogma. Nobody uses the left-hand exit, but they don’t understand why.

I took the metaphor on the surface level, though it also seemed to apply to the “right” and “left” paths indicated in many traditions — those of purity and passion, respectively. (In my frame of reference, these align with the white and red paths of tantra, also illustrated in the Hierophant tarot card.)

You can experience your Buddha nature either way. Yet to experience the left-hand exit, you would typically have to break a tradition, rule or dogma. But those are the only things that are stopping you. The door is there if you want it. Remember it’s there. Remember it’s open.

This is a radical teaching. It may not sound like it, though part of the message comes through who the teacher is. The teacher doesn’t make the message more correct, only more compelling. What he’s saying, as I understand it, is to remember that passion and worldly experience are valid teachers. You don’t need to take a conservative monastic path in order to learn and grow. You can live, and live consciously, and also grow, and express your soul’s intent.

Early on in the day, he urged his students to be extremely cautious around spiritual teachings; to scrutinize them like someone discerning whether gold is real before purchasing it. Again and again, his message was pay attention and think for yourself.

Another theme introduced early in the day was fear. Most spiritual teachers will tell you that you need to feel less fear. Dorje has a different spin. He first explained that fear is what biological instinct intends people to feel in the case of immediate danger. If there’s a tiger about to pounce on you, fear is a natural response. He called this existential fear.

Yet there are things in our current environment that we need to be fearful about, but which typically we are not. One example is climate change (a persistent topic for him). We really should be concerned about that, but for some reason it doesn’t register. He likened it to being told that in three months, a tiger will cross your path; most people would not worry, because it’s not going to happen for a while.

Concern about climate change requires thought and analysis. And this, he said, most people are not bothering with. This is the kind of fear you really need. What he did not say, though maybe he’s said it elsewhere, is that many people experience constant anxiety, which is a form of abstract fear that’s based neither on actual danger nor on a reasoning process. My impression is that anxiety is taking up most of the time, space and energy that would be better devoted to analysis.

“Meditation is not just about relaxing or helping us de-stress.” So said the Karmapa during a recent talk at Googleplex. Photo courtesy of Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism.

Instead, people cut themselves off and don’t feel much of anything. He likened this to a particular kind of lack of love he called apathy — the idea that, “It’s not my business, I’m not involved, this isn’t my responsibility.”

These become excuses for acting in unloving ways toward our neighbors. It’s not the overt kind of unloving, but rather refusing to be present or helpful when you’re needed.

It’s a big problem in the world where people tend to look after themselves and their immediate family, and look for excuses not to offer themselves to the wider community.

Then people see one another not caring. The next level of excuse becomes, “I don’t care because you don’t care,” and we end up with the world we have today. This is the logic of a world where love is severely lacking, and where we’ve limited our capacity to love.

Everyone “understands” this, because the excuse has a certain benefit — they don’t have to go out of their way, or take the time and energy required to help. And as a result, the world spirals into a dark place where compassion is often missing.

Later he returned to the theme of religion. One of the teachings of the Buddhist path is not worshipping what he called “mundane gods.” These he described as powers with whom we cut deals, make offerings and presumably receive protection from our misdeeds. Mundane gods get in the way of your connection to spirit or source — the Buddha within.

But he also was cautious about doing what he described as externalizing the Buddha. Whether you worship the Buddha as outside of yourself, or a mundane god outside of yourself, what you’re really demonstrating is lack of self-confidence.

Self-confidence is the most basic, useful kind of faith. When you lack that kind of confidence or faith, you’re likely to project it onto some external authority or object. That will in turn further weaken your self-confidence. So if you want to strengthen your confidence or faith, withdraw your worship of external gods and focus on your true inner nature. I would consider that a practical teaching — the best I’ve ever heard on the theme of confidence.

“We need to learn not to cling to temporary states of pleasure or happiness, but continue to seek absolute and permanent happiness. And since we cannot achieve this through material means, we must seek it within our own minds.” — H.H. the 17th Karmapa.

Part of the day’s program involved an introduction to what are called the three jewels of Buddhism — the three core concepts that compose the heart of the philosophy. These are Buddha, Dharma and Sanga.

Like all his other teachings, the Karmapa reinterpreted these somewhat, making them more accessible. Buddha is the teacher, the awakened one — which can refer to the guy himself, or to the Buddha nature within. You could think of the Buddha nature as loving self-awareness that embraces the world. Said another way, it’s being awake.

Dharma is your process along the journey; it’s what you actually do. Sanga is the family of your brothers and sisters already on the path. That could be quite a few people. In fact it could be everyone, so it may as well be anyone.

More traditional forms of Buddhism define these a bit more rigidly. For example, Dharma is sometimes defined as following the teachings of the Buddha. The Karmapa said that following the teachings and correct action are the same thing. Sanga is traditionally defined not as the community but as the priesthood. He expanded the idea a bit. The implication here is that we are all ministers of compassion; we are all teachers; Sanga is the community of those who are helping.

The afternoon session involved what Buddhists call the taking of refuge vows. I’ve been involved in my community as a kind of messenger or teacher for a long time. It was amazing being in a room of 1,500 people all of whom were promising to be more helpful.

Taking a guess, I would say that about half of us there were locals from in and around the Woodstock area. Imagine if all of those people really took that vow to heart; imagine if there really were a focus on loving self-awareness, love-in-action and honoring the family of those who are helping.

The 16th Karmapa, H.H. Rangjung Rigpe Dorje (1924-1981).

It would take far fewer people than that to completely transform a community — even a large one. Teaching through action (Dharma) has a way of spreading the light, slowly though it may seem.

Apathy deepens the darkness. Dharma is the correct response. It was very encouraging both to hear this and to know that the idea was being given a credible endorsement.

The thing I don’t understand about apathy as a choice; that is, about pretending that everything is someone else’s business, is that it’s so painful.

I may have to go out of my way in order to help someone, but I feel better when I do it. I would feel no better if I chose not to; personally, I am helpful to be helpful and because it feels good to do so. Helping, or acting in a loving way, spreads the positive energy. If someone has helped you, you’re more likely to help someone else.

Typically we get caught in the negative expression of this principle, the logic “Nobody wants to help me and I don’t want to help anyone.” We get this message a lot — it’s the very core of the neoconservative, Ayn Rand-based social theory that altruism does not exist. Take note that in fact altruism is self-serving because it makes you happier and helps you feel less isolated. Also, the real meaning of self-serving has a lot to do with your definition of self, which you might define as our collective existence.

The thing is, in our world, it takes a spiritual master on the level of the Karmapa to point this out, if anyone is going to believe it. We think we need a reincarnated expression of the Buddha himself to tell us that our lives will be better if we’re more willing to open ourselves up and offer our goodwill.

Hey, whatever it takes.

Lovingly,

![]()