When writer Mark Jaffe’s wife was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease, their sex life reversed polarities in the extreme thanks to one of her medications. Along the way to encountering unique insights, they eventually manage to find some equilibrium — and an unexpected shared purpose. In terms of clearing the ground and building anew, this story is perfect for the last Uranus-Pluto square. — Amanda P.

By Mark Jaffe for The New York Times

Somehow our three children were out of the house and otherwise engaged, leaving my wife and me a rare moment to ourselves. So I suggested to Karen that we take advantage by heading straight to the bedroom. She rebuffed me, asking, “How do men get anything done when they’re thinking about sex all the time?”

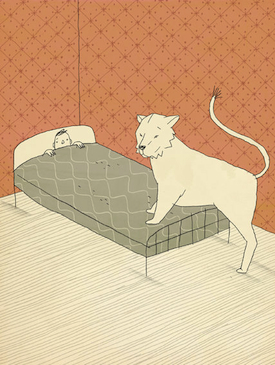

Illustration by Brian Rea for The New York Times.

Perhaps I could have come up with some explanation, but that’s not really what she was after. We had been married for 15 years by then and were raising three daughters.

In addition, Karen was a busy ob/gyn and part-time mohel. Our opportunities for having sex were scarce. Karen’s interest was even scarcer.

Friends who married long before I did told me that passion may wane in a marriage, but the love doesn’t have to. This was from couples who were still in their 20s.

I couldn’t believe it. To me, single and looking for love and sex, the two seemed so intertwined that I couldn’t imagine one ending while the other blossomed. Fifteen years into my marriage, I was hoping that just a touch of rekindled lust would enable my love to more easily flourish.

Karen wasn’t as concerned about commingling those twin emotions. Her point of view was reinforced each day at work when her patients complained how their interest in sex had faded to the background of life’s challenges.

For these women and my wife, there had to be the perfect confluence of events for sex to happen. My wife’s requirements were that her job had to be going well, the children didn’t need her attention, the house had to be clean, the temperature had to be between 76 and 84 degrees, and the Democrats had to control at least one branch of government.

Her patients would ask if there wasn’t some pill that would let them ignore the externals and give them back their desire. Karen would assess the acuteness of the concern and try to offer a solution, but she knew there was no magic pill. All she could do was commiserate.

She would come home and tell me how typical we were and that I would just have to deal with my oversize libido like all the other unsatisfied married men out there.

Then we learned she had Parkinson’s.

Suddenly we were faced with new challenges that completely outweighed any issue of unequal sexual desire. Our fantasy of the next 35 years had included Karen staying in a job she loved for as long as she wished and then for the two of us to shift to a retirement of travel and newfound hobbies.

That image was replaced by one depicting her early exit from the job she loved and a retirement filled with financial concerns, frequent doctor visits and uncertain health.

Our first adjustment was to try to live in and enjoy the present. It took a few months of finding the right medication and dosage, but since Karen’s Parkinson’s was in the early stages and could be controlled, it wasn’t long before her natural optimism took over.

For now she would be living her same life, with the minor addition of keeping a secret (so as not to alarm anyone or harm her career), and taking some pills each day.

Those pills would change our life more than the Parkinson’s.