By SAM ROBERTS | Link to original

Beatrice Trum Hunter, a Brooklyn-born public school teacher who transplanted herself in midlife to a sylvan sanctuary, where she compiled what was heralded as the nation’s first healthful natural foods cookbook, died on Wednesday in Hillsborough, N.H. Having practiced what she preached, Mrs. Hunter lived to be 98.

Her death was confirmed by her nephew Dr. Dan M. Granoff.

Beatrice Trum Hunter’s passion for health was inspired in high school by a book that described American consumers as unwitting guinea pigs for the food, drug and cosmetics industries. Credit Robert Granoff, via AP.

Inspired in high school by a book that described American consumers as unwitting guinea pigs for the food, pharmaceutical and cosmetics industries, Mrs. Hunter became an autodidactic apostle of whole grains, honey and vegetable oils as substitutes for refined flours, sugars and animal fats.

More prominent public health pioneers, including the environmentalist Rachel Carson and the nutritionist Adelle Davis, would seek her advice about artificial food additives and pesticides and incorporate her research and expertise into their best-selling books.

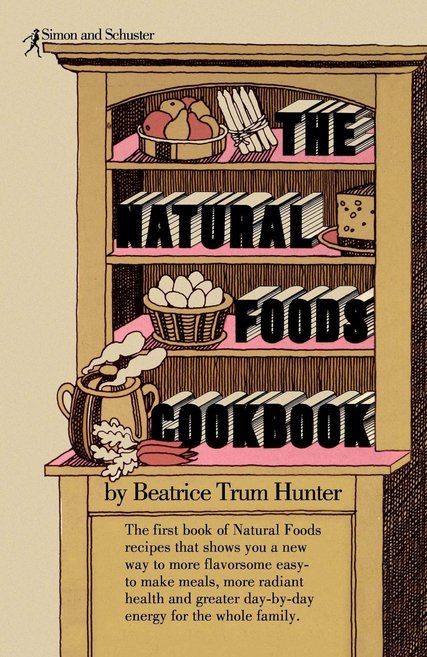

Mrs. Hunter published her prototypical “The Natural Foods Cookbook,” the first of 38 books, in 1961 — fully a decade before the movement was popularized by more widely circulated recipe collections like “Diet for a Small Planet,” “Moosewood Cookbook” and the first natural foods cookbook published by Rodale Press, which grew into a health and wellness publishing conglomerate.

Warning against the artificial additives, processed foods and preservatives that were proliferating in the American diet, Mrs. Hunter wrote, “Foods treated in this manner may appear brighter and last longer, but the people who eat them don’t.”

She for one lasted longer, she recalled, in part because she had changed her own eating habits as a teenager after feeling fatigued and suffering from straggly hair and bad skin.

Blaming a terrible diet, she had also endured a childhood bout of rickets, which can cause bone deformities, stemming from a vitamin D deficiency. Vitamin D can be derived from fish oil, egg yolks, milk and sunlight.

Mrs. Hunter published her prototypical “The Natural Foods Cookbook,” the first of 38 books, in 1961. Simon and Schuster.

Then she read “100,000,000 Guinea Pigs,” a best-selling book by Arthur Kallett and Frederick J. Schlink published in 1933 whose title refers to the size of the nation’s population at the time. The book was considered a catalyst for the creation of the Food and Drug Administration.

“The first thing I did was to cut out sugar,” Mrs. Hunter told Yankee magazine in 2015, “and then I began to use more whole grains and more fresh vegetables and fruits.”

After teaching visually impaired and intellectually gifted students in New York and New Jersey, she decamped permanently in 1955 with her husband, John, to a white two-story farmhouse on 78 acres that they had bought for $1,800 six years before in Deering, a southern New Hampshire village of about 300 people.

They were joined there by her mother-in-law, Lotte Jacobi, a German Jew, who had fled the Nazis in 1935. A renowned photographer, Ms. Jacobi opened a studio in Deering.

The couple later turned the property into an inn for fellow naturalists and photographers who, unafraid of roughing it, also got to feast on Mrs. Hunter’s recipes. (The inn was so rustic that it was nameless.)

Beatrice Josephine Trum was born on Dec. 16, 1918, a month after World War I had officially ended, in Brooklyn to Gabriel Trum, who worked as a cutter in a silk-dyeing plant, and the former Martha Engle.

Neither of her parents had gone beyond the sixth grade, she said, and after she graduated from Richmond Hill High School in Queens they agreed to send her to college only reluctantly.

She enrolled in Brooklyn College and graduated in 1940 with a bachelor’s degree in English literature. Accompanying a blind student on the subway to and from campus, she had learned to read Braille and became disposed to teaching visually impaired students.

From Brooklyn she went on to study at the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Mass., and later earned a master’s from Teachers College at Columbia University. She taught in New Jersey and New York City schools until she and her husband, a fellow teacher, moved to New Hampshire.

Her marriage to John Hunter, who helped manage the inn and later became a rare-coin dealer, ended in divorce in 1977. An older sister died earlier. Her three nephews are her closest survivors.

From her house, which was heated only by a wood-burning stove, Mrs. Hunter wrote books on her IBM Selectric typewriter. They included “Gardening Without Poisons” in 1961 and “Our Toxic Legacy: How Lead, Mercury, Arsenic, and Cadmium Harm Our Health” in 2011.

She was also the food editor of Consumers’ Research Bulletin magazine, which had been published by Mr. Schlink, an author of the compelling book she had read in high school. In 1973 she appeared on the Boston public television station WGBH, delivering mini-lessons on nutrition on a program called “Beatrice Trum Hunter’s Natural Foods.”

After her mother-in-law became incapacitated and Mrs. Hunter inherited her camera collection, she learned photography and captured artistic images of ice crystals on her windowpanes as a hobby, but never lost her fascination with natural foods.

“I’m self-taught,” she said. “I’ve never hesitated to ask for help from reliable sources when I’ve needed it. What to call me? Call me a concerned consumer.”